Sustainability: our role as individuals.

How do we feel, as individuals, about sustainability? Do we take responsibility for our behavior and daily choices or, as opposed, we have the impression that it is something that concerns “other people”, politicians and those working in the United Nations mainly?

I can’t help thinking about this every time I read or listen somebody talking about sustainable development. It looks like if it is some kind of policy that has to be implemented internationally or even worldwide but the “bad guys” (institutions, politicians, multinationals, Europe, United States and the so called developed nations) refuse to take the necessary steps to foster a significant change because they do not want to give up on their status quo.

www.batr.org

In this post I would like to focus on a different approach: how small personal actions can contribute to sustainable development.

Some argue that the current system where economy is based on endless growth needs to be replaced if we want to achieve a sustainable development. But, replaced for what? What are the alternatives? Is it only the Economy that is based on endless growth, or is it our human nature to always want more? When are we going to be able to say “I have enough”? Is that even possible in an economy that is based on ruthless competition? We live in an era of abundance, like never in history before, and yet we don’t seem to be satisfied.

Uruguay’s President, Jose Mujica, speech at the Rio+20 summit (the United Nations conference on sustainable development) proposed a different type of discussion over the model of development: as it is well known that the planet do not have the material elements to enable 7 billion people to enjoy the same level of consumption as the most affluent western societies, Jose Mujica proposed a model where development has to work in favor of human happiness by establishing the essential preconditions for human beings to flourish and achieve wellbeing.

Based on the above, I believe that we, as individuals, have an important role to play. We should reconsider our lifestyle, assume part of the responsibility and start taking the necessary steps and personal actions in order to contribute in creating a more responsible business and community. Of course policy and institutions are crucial, but structural change is more willing to happen when people fight for it. A societal change is a transformative process where small actions are fundamental. When practiced consistently, small actions lead to value change that also motivates broad action.

While this may sound utopic or at least difficult to achieve, more and more people, businesses and communities around the globe are finding that a little change in attitude and commitment can make a real impact. Many cases can be found online, but just to provide one example, I found particularly interesting the report on community initiatives across the United States as it demonstrates the diversity and breadth of approaches that citizens and communities are using to promote economic health, environmental quality, and social equity. [1]

So let’s grab the bull by its horns and let’s start taking the small steps that makes us feel recognized and may also inspire others to take small steps towards a more sustainable lifestyle. The challenge is enormous and in order to succeed, we must realize that although small actions can seem insignificant, it is in fact critical.

So let’s grab the bull by its horns and let’s start taking the small steps that makes us feel recognized and may also inspire others to take small steps towards a more sustainable lifestyle. The challenge is enormous and in order to succeed, we must realize that although small actions can seem insignificant, it is in fact critical.

If we, as individuals, feel personally involved and committed to sustainability then we are laying the foundations to embrace a change on a societal level.

Reference:

[1] Sustainability in action: Profiles of Community Initiatives Across the United States, Revised/Updated edition: June 1998. Urban and Economic Policy Division, UE EPA: CONCERN, Inc.; Community Sustainability Resource Institute.

Development Aid: Empower not Prescribe

“Aid appears to have established as a priority the importance of influencing domestic policy in the recipient countries.”

Benjamin F. Nelson

Linda Polmann in her speech for TEDxHamburg describes international aid as an industry. It focuses on investment but involves other industries to benefit from investment return. Today aid industry provides work places to thousands of people all over the world and grows significantly from year to year.

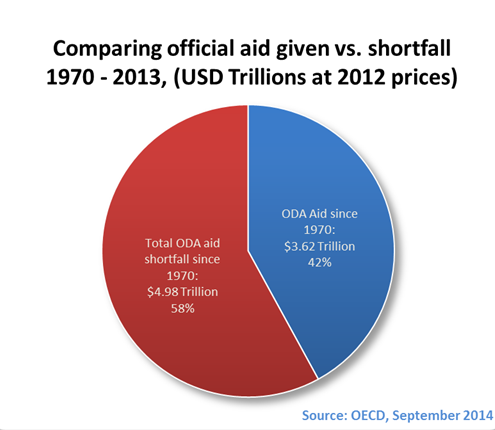

Meant in definition to be voluntary and selfless, development aid through its efficient application should aim for further aid reduction. But instead of being cut development aid today plays important role on world markets. After its decrease in the years 2011 and 2012 official development aid last year achieved the high record of $134.8 bln and showed the growth of 6.1% compared to 2012.[1] These figures not only show the increasing readiness of countries to help in developing sustainable future for all. But also the raising influence of a donor country on economic, cultural and political spheres of a recipient country when providing development aid. Facing the increase of world’s official development aid special attention should be drawn to the ties for recipient countries which accompany such aid.

The idea of voluntary financial help sounds tempting for aid recipients until the rules of the game are imposed. In the book “Dead Aid” Dambisa Moyo says “The mistake the West made was giving something for nothing.” But was there really nothing in return? Not only development aid maintains dependency but also forces recipient countries to implement certain change which can hardly be beneficial for aid recipients.

Source: http://buildingmarkets.org/blogs/blog/2012/06/14/how-deep-doth-run-the-question-of-local-procurement/

Starting with misfeasance I will give an example of World Development Movement campaign organization report in 2005. It informed about British government pushing aid recipient countries to privatize water services, even if with low benefit for them, through paying British companies with financial aid resources.[2]

Though the example speaks for itself I am talking not only about misuse of aid money. The whole attitude of imposing donor beneficial conditions or restrictions for receiving development aid is wrong. Introducing certain conditions gives the semblance of partnership between donors and recipients. While partnership is about fair participation of both parties. Recipient countries are rightful owners of financial aid but when accepting conditions they have less control and decision-making on how the aid is distributed. So setting less conditions does not mean decreasing control of money use but rather wise coordination of money flows.

The necessity to raise recipient countries’ voices was introduced in Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005. Here the idea was presented that recipients should elaborate their own strategies for development while donors should align behind those strategies and use local resource systems. Then Accra Agenda for Action in 2008 followed raising the question of more deep and strong participation of recipient countries in aid distribution.

It was introduced by inter Press Service based on a U.N. study on African economies that imposing restrictions or conditions to aid recipients reduces the value of aid by 25 to 40 percent.[3] So if not concentrating on gaining advantage from development aid recipients, ways of using local resources would be considered in more details. And then a sound voice of recipient should be heard.

Interpress Service News notes the example of Eritrea given by Njoki Njoroge, director of the 50 Years is Enough campaign. Eritrea found out that it would be cheaper to build its railway with local resources and experience than be forced to spend development aid on conducting its conditions such as hiring foreign architects, experts, engineers.[2]

Providing conditions or restrictions to receive development aid not only promotes ties but forces developing countries feel obliged to accept the posed rules. But what if the wanted changes do not fit in the recipient’s policy? What if the local specialists can contribute more than expected? What if non of the already experienced development strategies fits? What if a recipient country’s society does not want the rapid change? What if an aid recipient proves to have better capability to manage the aid use?

William Easterly says there are two types of approaches to organization of development aid: a top-down imposing approach from Planners and a grass-root bottom-up approach from Searchers. He says:

“A Planner believes outsiders know enough to impose solutions. A Searcher believes only insiders have enough knowledge to find solutions, and that most solutions must be homegrown.”[2]

It would be false to say that a Planner does not have good intentions, enough education or capacity to bring ideas into another society. But the system a Planner was brought up in sets limits to his ideas and introduces what is right and what is wrong in his certain society. While mindset of a member of another society may vary much from rights and wrongs of a Planner.

Since Paris Declaration of Effective Aid the certain progress has been made in the field of empowering aid recipients with their own ways to develop and breaking tied aid. The results of research on progress of implementing Paris Declaration showed that by 2010 the proportion of aid recipient countries who elaborated sound national strategies for development has more than tripled since 2005.[3] But today the question remains about if those strategies are implemented effectively and how to make voices of donors and recipients equal in the process of aid distribution.

Tied aid brings limits to collaboration between donor and recipient countries which results into low effectiveness of aid distribution and low participation of aid recipients. Therefore conditions and restrictions for development aid should be gradually eliminated in ongoing aid campaigns and should not be represented in newly introduced aid programs. According to Interpress Service News several countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, United Kingdom today are step by step breaking away from the idea of tied aid.[2]

Development aid has its core meaning in bringing new into real. In many cases the effective way to have sustainable aid results is to empower local people. And the way to do so is to take local policy more seriously. To listen to the voices of local officials, activists, organizations, citizens. To give them the opportunity to build their next day the way they want to see it.

Bibliography:

1. Provost, C. (2014) “Foreign aid reached record high” in Guardian, April, 8. Retrieved: 28/12/2014 from http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/apr/08/foreign-aid-spending-developing-countries.

2. Shah, A. (2014) “Foreign aid for development assistance” in Global Issues, September 28. Retrieved: 27/12/2014 from http://www.globalissues.org/print/article/35.

3. 4th High level forum on aid effectiveness (2011) “Aid-effectiveness 2005-10: progress in implementing the Paris Declaration” Busan, Korea, November 29 – December 1. Retrieved: 28/12/2014 from www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/48734301.pdf.

Intro

Dear readers,

My pleasure to find you reading this.

Here are a couple of words about who is Tatsiana Prokharchyk and what this blog is going to be about.

My path to EOI has been long and thorny. It took me all in all about 13 months of creating convincing applications and showing my enthusiasm when interviewed to obtain my scholarship, posing convincing reasons for my boss to let me go, arranging dozens of assuring papers to obtain study visa and making EOI application to finally start my IMSD studies in October 2014. So there is no need to explain how willing I was to take IMSD course.

Source: http://www.conceptelemental.com/countries.html

My studies at TU Dresden opened new knowledge perspectives and brought my scope to the energy field. So when graduated from Belarusian National Technical University with my BSc in Energy Economics and Engineering I already knew that energy is the sector I would like to work in. Two years of work as an energy manager at the Ministry of Energy strengthened my confidence even more and gave possibility to narrow my objectives. Here am I at EOI opening new issues of interest for me, broadening my perspectives and forming the base for my further career step. I am much interested in energy for sustainability and development. And I can feel that this topic has just started to lift the curtain for me.

Well, I could start explaining my objectives and positions here. But I will let this introduction be short. Hope I managed to catch your interest. If so you are welcome to read my further posts and pose your questions and comments.

This is my first experience writing a blog and I am very enthusiastic about how it goes. So, wish me good luck and enjoy further reading.

Yours,

Tatsiana

Welcome to my Blog

After leaving the “study bench”(literal translation from Dutch), more than 6 years ago, and having worked in very diverse areas (from truck driver to Investment Promoter), here I am again, faced with a new challenge. Why leave the love of my family, the comfort of a stable job and Curaçao, a great island in the Dutch Caribbean?

The main reason for this, is my growing questions about the world, poverty, fair business practices etc. Why was I getting the impression that most of the companies I knew talked about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) but had an approach close to Philanthrophy? Would they use these acts only as a marketing tool (“Greenwashing”)? What if CSR includes much more than that? These questions made me start reading more about CSR, attending lectures and seminars and finally I took the step to follow the International Master Sustainable Development and Corporate Social Responsibility at the EOI Business School in Madrid. Currently the master focusses more on Sustainable Development and as of February 2015 we will focus on CSR.

The process of discovering that I know so little about the world is fascinating. I hadn’t realised before that I was so influenced by the media. My perceptions have been challenged by for example: not all the Aid for Africa propaganda gives a real representation of the local situation. Take a look at this hilarious way of criticising the stereotyping of poor South Africans:

I had no idea that some African economists would prefer to refuse development aid, which has made me a great admirer of Dambissa Moyo. Sending help in the form of tangible stuff (food, medicines, blankets, tents) was, I beleived, the only and most efficient way to help in a disaster. But what if: “Relief is the enemy of recovery” (prof. O. Koeningsberger)? I never realised that the image of a white teacher (mostly in her early twenties), giving English lessons to a group of African children doesn’t have to be the standard picture.

I can relate so much to these post colonial development issues that arose after many African countries became independent. Curaçao and Bonaire, among the 6 islands in the Dutch Caribbean, still within the Kingdom of the Netherlands (the first as an independent country and Bonaire as a municipality), are the two Dutch islands I can relate with. How do the relationships with our Mother Country, The Netherlands, influence our sense of nationalism? What do the African Post Colonial thinkers have in common with our own Caribbean writers (Tip Marugg), poets (Pierre Lauffer) and scholars (Frank Martinus Arion) having an opinion about these relations? Expect to read more about Dutch Caribbean colonial thinkers and the colonial relationships I experience in my following posts.

This has been my dose of reality checks so far….Reality checks over and over again. I can’t wait to dive into the CSR world in February and get surprised even more. I’ll be posting on subjects of my interest from time to time, starting with a series of slogans derived from the class Natural Resource Management, my view on how Urban planning influences inequalities in a city and also on my feelings as a ‘Curapolitan’.

I’m looking forward to your ideas and comments.

Happy reading!

Esther Sedney

Empresa Innovadora en el Sector del Medio Ambiente. El Caso de JACASPE.

¿Qué es JACASPE?

JACASPE es una empresa franco-española online dedicada al comercio de productos gourmet de la región de los Pirineos tanto francés como español. Los productos ofrecidos son artesanales, naturales y ecológicos y son comercializados en Francia y España. Uno de los objetivos de la empresa es dinamizar el comercio de productos tradicionales y ecológicos de pequeños productores

Logo JACASPE. Fuente: JACASPE

¿Por qué es JACASPE una empresa innovadora?

La principal innovación de JACASPE es su trabajo a nivel regional, que en su caso es además transfronterizo. Esto es una novedad en empresas del sector del desarrollo rural donde las fronteras administrativas suponen una barrera por temas burocráticos y de subvenciones principalmente. Trabajar a nivel regional no solos les ha permitido abrir su mercado a dos países sino, a nivel social, el desarrollo de la región de los Pirineos como una unidad y no como parte de dos países.

Por otro lado, al trabajar directamente con granjas y productores han eliminado los intermediarios entre el productor y el comercio. Esto supone una innovación para los pequeños productores que no pueden distribuir directamente pudiendo expandir su mercado sin aumentar costes.

JACASPE se constituye de este modo como una empresa innovadora en el sector del desarrollo rural y medio ambiente. Su modelo de comercio a nivel de región podría ser importado a otras empresas, no solo de comercio de productos agrícolas ecológicos sino a todos tipos de empresas, ayudando de este modo un desarrollo en el medio rural de forma integrada. Esto supondría un gran avance a nivel regional y un acercamiento al modelo de desarrollo que la Unión Europea propone en sus programas.

Para conocer más sobre JACASPE y los productos que comercializa visita su página web: http://www.jacaspeproductosregionales.es/

Partnerships for innovation in access to basic services

As we approach 2015, the deadline for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, it is clear that solid progress has been made in addressing access to basic services such as health, education, energy and water and sanitation. However, we also know that success within countries and regions has been uneven and that important efforts are required to ensure that basic services reach “the last mile” of the population. This category includes those who live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than $1.25 a day, many of whom are further marginalised as a result of factors such as gender, ethnicity and geographical situation.

In a recent research study undertaken for the Inter-American Development Bank’s Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF) (MIF/IDB) by the Innovation and Technology for Development Centre at the Technical University of Madrid (itdUPM) we have found that new forms of multi-stakeholder partnerships can offer innovative, locally relevant and sustainable solutions to address gaps in access to services for the most poor and vulnerable. These arrangements pool the expertise, resources and knowledge of different actors in the public, private and civil society sectors, and incentivise those living at the “base of the pyramid” to assume active roles in service provision. Furthermore, their focus is not simply on ensuring wider access, but also on offering a good quality service.

The study, which was carried out in collaboration with Building Partnerships for Development in Water and Sanitation (BPD), Enlace Hispano America de Salud (EHAS) and ONGAWA, looks at lessons from five partnership models that are working to address gaps in the delivery and quality of basic services to vulnerable groups. The models include:

Luz en Casa (Cajamarca, Peru): A programme developed by the Acciona Microenergy Foundation which has developed a social enterprise, Acciona Microenergy Peru, that delivers off-grid electricity in remote rural areas through a pay-for-service model centred upon close interaction with the local community. With the installation of 3.000 Solar Home Systems (SHS), the programme has enabled an increase in family incomes due to reductions in energy costs, as well as extra time for productive activities.

TulaSalud (Alta Verapaz, Guatemala): A partnership that promotes health service improvements for isolated rural communities using Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to train local nursing personnel and provide telemedicine. The e-health programme has trained almost 1.300 professionals and resulted in 195 local community tele-facilitators attending to a population of some 330.000 inhabitants with maternal mortality rates showing clear improvements.

Inclusive Sanitation Markets (Cochabamba, Bolivia): An ecosystem for market-driven sanitation services in peri-urban areas facilitated by the international NGO Water For People. The initiative installs dry ecological toilets which are about 40% cheaper than traditional flush toilets. As well as promoting offers adapted to family needs using social marketing campaigns, a quality low-cost service offer is being developed with local entrepreneurs.

Ciudad Saludable (Peru): A holistic solid waste management system composed of multiple partnerships along the waste management value chain with the socio-economic inclusion of recyclers. In 2010, Ciudad Saludable established 35 microenterprises, including greenhouses, production plants for organic fertilizers, paper recycling companies and sanitary landfills, creating jobs for 320 people in 20 cities and benefiting three million people in Lima.

Washing area in Community Ablution Block Number 2, Johanna Road informal settlement, eThekwini (South Africa)

eThekwini Water and Sanitation Unit (Durban, South Africa): A municipal water and sanitation unit working to expand services through community outreach activities and partnerships with academia, the private sector, and international foundations. Recent coverage figures show that 92% of the population now has access to basic water and 76% to basic sanitation services.

The study suggests that the success of these partnership initiatives rests upon 4P innovations:

1. Product innovations: adapting or building upon existing products or services, often around the use of technology, and ensuring that these are part of overarching programmes or systems rather than standalone devices or interventions.

2. Process innovations: using flexible collaborative processes in which actors from the public, private and civil society sectors work together to provide services. Ongoing review systems that encourage feedback from all actors are also drawn upon to make improvements.

3. Position innovations: adopting an inclusive pro-poor approach in which service solutions are carefully tailored for and co-designed with users. Working closely with government, this re-positioning of hitherto marginalised collectives in service models involves important efforts to ensure attention is given to the particular needs of different groups.

4. Paradigm innovations: changing mental models by redefining the overarching systems in which services are delivered and re-conceptualising the role of users as active players in the development and operation of basic services.

The emphasis on understanding and engaging end users in service models is at the heart of their success. Such an approach recognises the multifaceted nature of “base of the pyramid” populations and has enabled the identification and mobilisation of previously unacknowledged local resources and skills, including community knowledge, expertise and entrepreneurial abilities that can support improved access to basic services. In this sense, the paradigm innovations highlighted above endorse broad concepts of inclusive business and social entrepreneurship which reposition end users as active agents (rather than beneficiaries or recipients) in the creation of sustainable solutions for the provision of basic services.

While replication and scale-up of such models is desirable, careful attention needs to be given to the study of contextual variables and cultural appropriateness. Furthermore, it is also important to ensure that adaptation addresses whole value chain systems and financial sustainability from the start.

Montes de Socios: social entrepreneurship for rural development

Many lands in Spain, especially forests, are not property of one person but rather of a group of people. This type of joint ownership has different names depending of the region but almost all of them share the same characteristic, the woodland is pro indiviso, which means that the property is not divided between its owners. They can have different shares of the land property but there are no demarcations dividing what belongs to each member.

The property passes from fathers to sons, multiplying the number of owners with each generation and, in most of the cases, these transfers are not documented, being the title holders people dead 100 years ago. Hence, the cadastre shows that the land belongs to nonexistent companies, deceased owners or entities that do not accurately represent the legitimate owners.

This complex property regime extremely complicates the management of the forests, having to face a lot of administrative obstacles in order to complete any kind of procedure. The result is woodlands managed and exploited in a way far from ideal or completely abandoned in many cases.

Pedro Medrano, as part of the Sorian Forest Association (Asociación Forestal de Soria) has being working to solve this issue. He launched, through the initiative Partners’ Woodlands (Montes de Socios), a management model based on traditional mechanism that establishes clear partnered ownership and management of the forest.

Pedro Medrano, as part of the Sorian Forest Association (Asociación Forestal de Soria) has being working to solve this issue. He launched, through the initiative Partners’ Woodlands (Montes de Socios), a management model based on traditional mechanism that establishes clear partnered ownership and management of the forest.

These model, the Management Boards (Juntas Gestoras), were integrated in the Spanish legislation trough the 2003 Forestry Act (Ley de Montes). These Boards allow the co-owners of woodlands to act as a single legal entity, making possible their management and conservation, adding value to otherwise abandoned land. But also become a liaison between city and countryside people that have inherited the ownership from ancestors which were fellow countrymen, creating a renewed interest and a sense of connection to the countryside.

Partners’ Woodlands also works on the recuperation of the documental base of the forest confiscation; offers guidance for forest management and conservation and promotes the creation of legal frameworks for co-owned woodlands.

At present day, many Management Boards have been constituted through Partners’ Woodlands: 34 in Soria, 9 in Asturias, 2 in Guadalajara and 1 in León.

A two page article (present in front cover) was dedicated to the initiative in the newspaper EL País the 28th November 2011. The initiative has been also awarded with the Dubai International Award for Best Practices 2012. In addition Pedro Medrano has become, in February of this year, fellow changemaker of Ashoka.

Pedro Medrano and Cándido Moreno show a record of a co-owned woodland's owners. Source: El País Photo: Carlos Rosillo

Related Websites

European Commission 2030 Proposal – Target Stringency for EU ETS and ESD

On 22 January 2014 the European Commission proposed a new binding reduction target for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, calling for a 40% reduction from 1990 levels to be met through domestic measures alone.[i] The annual reduction in the cap would be increased from 1.74% now to 2.2% after 2020, and there is also a call for emissions outside of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) to be cut by 30% below the 2005 level, which is to be shared across the Member States.[ii]

On 22 January 2014 the European Commission proposed a new binding reduction target for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, calling for a 40% reduction from 1990 levels to be met through domestic measures alone.[i] The annual reduction in the cap would be increased from 1.74% now to 2.2% after 2020, and there is also a call for emissions outside of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) to be cut by 30% below the 2005 level, which is to be shared across the Member States.[ii]

There are some critics to the European Commission’s proposals, though many do want to implement some of the proposals and believe that they are a step in the right direction in order to achieve long-term emissions reductions. Specifically, Carbon Market Watch claims that the 40% target proposed is not ambitious enough in order to meet targets of 80-95% reductions by 2050.[iii] They also point out that the use of international offsets needs to be reevaluated and EU-wide quality restrictions must be applied in order to protect European competitiveness.[iv] In their report they explain, “Despite the domestic nature of the EU’s 2030 GHG target, international offsets may be used by Member States that want to increase their own GHG targets beyond the EU-wide GHG targets. Between 2013 and 2020 more than two thirds of all issued offsets will come from large-scale business- as-usual energy projects that do not represent real emissions reductions because the projects would have gone ahead anyway. Instead of investing in clean energy projects in Europe, businesses are spending money on purchasing offsets from projects in developing countries that would have been built anyway. This is hardly a way to protect European competitiveness.”[v]

On 21 March 2014, the European Council convened for their Spring Meeting and reviewed the Commission’s proposal to conclude that the new framework should be based on the following principles[vi]:

- further improve coherence between greenhouse gas emissions reduction, energy efficiency and the use of renewables and deliver the objectives for 2030 in a cost-effective manner, with a reformed Emissions Trading System playing a central role in this regard;

- develop a supportive EU framework for advancing renewable energies and ensure international competitiveness;

- ensure security of energy supply for households and businesses at affordable and competitive prices;

- provide flexibility for the Member States as to how they deliver their commitments in order to reflect national circumstances and respect their freedom to determine their energy mix.

As can be seen from the proposal in January, 20% reduction targets in 2020 would increase to 40% by 2030, and this is supposed to place the EU on track to meet the 80% reduction by 2050

The Council doesn’t specifically mention anything in regard to applying stringent targets for the EU ETS and ESD, but they do seem to comply with the ideas and proposals set forward by the Commission in stating that there should be further coherence between targets and ETS reform should play a central role in achieving their objectives. An agreement was made to make a final decision regarding the framework by October 2014 at the latest.[vii]

One of the major concerns for many is the ineffectiveness of carbon markets and the EU ETS due to the extreme surplus of emission allowances and international credits that has grown since 2009. At the start of Phase III of the EU ETS in 2013, the surplus stood at almost two billion allowances, and the European Commission’s anticipation is that although the surplus will discontinue to grow, there will not be much of a decline in allowances.[viii] Having so many allowances in the market risks damaging the orderly function of the carbon market, and furthermore presents ample risks for the ETS in it’s capability to meet demanding emission reduction targets in future phases..

Because of the over supply, current carbon prices are far from the prices ETS projections are based on. Therefore, the situation might be a call to transition focus on the Effort Sharing Decision (EDS) as well as the ETS. In the Energy Roadmap 2050 that was composed in 2011, it can be seen that they project the “contribution to the emission reductions [to be] driven by the ETS sectors which decrease emissions by 48% between 2005 and 2050; on the contrary the non-ETS sectors reduce by 21% compared to 2005.”[ix] Today we can see that the non-ETS sector target has been adjusted in January’s proposal, but clearly prevailing policy is not adequate and the proposals of late have been a testament to that.

Making a new legally binding reduction target that is to be met through solely domestic measures is telling, because there’s potential that the European Commission has learned from the past and understands the importance of making a compulsory, more aspiring objective outside of the ETS in order to hedge risk of it’s failure. [P1]

[i] European Commission. 2014. 2030 climate and energy goals for a competitive, secure and low-carbon EU economy. [press release] 22 January 2014

[ii] European Commission. 2014

[iii] Carbon Market Watch. 2014. European Council must close loopholes in the 2030 climate & energy framework. [press release] 7 March 2014.

[iv] Carbon Market Watch. 2014

[v] Carbon Market Watch. 2014

[vi] European Council. 2014. Conclusions – 20/21 March 2014. [press release] 21 March 2014.

[vii] European Council. 2014

[viii] Ec.europa.eu. 2014. Structural reform of the European carbon market – European Commission. [online] Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/reform/index_en.htm [Accessed: 2 Apr 2014].

[ix] European Commission. 2011. Energy Roadmap 2050 – Impact Assessment and Scenario Analysis. [report] Brussels.

[P1]The door is still open for international credits but subject to an international agreement and further tightening the caps.

The Energy Efficiency Directive and Possible Implications on the EU ETS

At present, energy efficiency is considered one of the most crucial pillars to EU policy. The more efficiently energy is consumed and produced, the higher the possibilities for cost reductions at consumer as well as at industry level. Furthermore, savings can then lead to increased competitiveness of industry and the EU economy as a whole. By 2008, the EU recognised that the 20-20-20 target of a 20% reduction in energy consumption would not be met. Previously, energy efficiency targets were not transferred into binding legislation – this resulted in slippage and underperformance. In order to tackle this problem with a more fundamental approach, the EU agreed to put together an ambitious plan to meet this goal. The result was the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) of 2012.

The EED came into effect in December 2013 with all member states expected to enforce the required measures by the summer of 2014. It aims to fill the gap between existing framework directives and national policies on energy efficiency. The main objective of the directive is to ensure the implementation of additional measures that will enable the 2020 goal to be achieved. Measures, which focus on utilities and building, that are key to the EED include:

- Renovation of 3% of the total floor areas of public sector buildings each year[1]

- Energy audits and management plans for large companies[2]

- The requirement of energy companies to reduce energy sales by 1.5% every year among their customers. To reach this target, improvements such as combined heat and power generation, fitting double-glazed windows and insulation for roofs have been proposed.

As with the introduction of any new policy, there has been discussion of how the EED will affect existing directives aimed at reducing emissions levels within the EU. The impact of the EED on the EU ÊTS – the World’s leading emissions trading scheme – has been highlighted as a cause for concern.

As implementation of the EED is predicted to lead to overall reduced energy consumption, this will in turn cause a reduction in carbon emission levels (a similar scenario has already been experienced during recent economic downturn when overall output declined). A reduction in emissions levels and demand in the market would have knock-on effect of reducing the scarcity and the price of allowances on the carbon market. Model scenarios commissioned by the EC, have shown that in some cases carbon prices could drop to zero – causing the market to collapse and the savings made by the EED to be reversed. This has led to calls for the EUs “business-as-usual” strategy to be examined more closely.

The EU has recognised the challenges that this poses and state that it is committed to monitor the situation carefully. The EC has suggested lowering the cap at a higher rate (2.2%) from 2021 on a yearly basis as part of their 2030 targets, however this has been criticized for the time it would take to reduce the surplus. There have however been increasing calls for direct action and for adjustments to be made to the ETS in order to allow it to adequately accommodate the EED in both the medium and long term. Many have called for the strengthening of the ETS cap to counterbalance the effect of increased allowances being issued through EED based initiatives. Others have called for permits to be withheld from the next ETS phase. The UK based carbon think-tank “Sandbag” has recommended that the ETS set aside 1.4 billion tonnes of permits rather than “backload” from phase three to increase competitiveness within the market. To date, the EU has

In order to accelerate the EUs energy efficiency drive, the EED would appear to be an appropriate device – energy efficiency measures can be made relatively inexpensively and have a positive economic impact. As the supply of allowances is fixed years in advance, it is difficult to calculate the exact impact and prepare for unknown variables such as EED on the ETS. However, evidence suggests that that the ETS will need to adapt in order to maintain a buoyant market.

[1] Article 5, Understanding the energy efficiency directive http://www.eceee.org/policy-areas/EE-directive

[2] Article 7, Understanding the energy efficiency directive http://www.eceee.org/policy-areas/EE-directive

CERs and the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)

The EU ETS was devised as one of several strategies to meet the European Kyoto Protocol target of an 8% reduction for the period 2008 – 2012, and now for the more ambitious EU target of 20% by 2020. Policies regarding renewable energies and energy efficiency, agriculture, and transportation, (to name a few), also contribute to European emissions reductions goals.

The EU ETS covers approximately 45% of total European Emissions (EC, 2013), including emissions from the power sector, aviation (for flights within Europe, though the original proposal covered international flights as well), and has successfully managed to integrate environmental costs into financial cost structures, thus ensuring that emissions are allocated a cost which will be taken into consideration during planning. This puts a monetary value on emissions, and incentivises reductions, and investment into R&D of more efficient, and less pollutant technologies.

In order to provide some flexibility, the Linking Directive (2004) was brought into effect, which allows for the use of Kyoto Protocol flexibility mechanisms, and serves to connect the EU ETS with the international carbon market, and increases international cooperation. The incorporation of these mechanisms allows countries to meet some of their reductions commitments through obtaining Certified Emissions Reductions (CERs) – to focus of the post – and Emissions Reductions Units (ERUs) through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI), respectively. Both mechanisms involve the emissions reductions projects, the former in non-annex I countries (developing countries and LDCs), and the latter in annex I countries (i.e. those countries with binding KP targets) (UNFCCC, 2014).

Unfortunately, these mechanisms, which were designed to complement domestic reductions options, increase cost efficiency, and promote international efforts to reduce, have had unexpected results on the effectiveness of EU ETS.

Firstly, instead of supporting domestic reductions strategies CERs came to substitute for domestic action to meet international requirements. In terms of global emissions targets, provided the projects meet standards for environmental integrity, global targets will be met. However, an excessive use of CERs by EU countries for projects in non-EU countries undermines the EU reductions goals. In order to stay on track with for these goals, a limit on the use of CERs was put in place, forcing countries in the EU to consider domestic reductions. Unfortunately, difficulty in determining an adequate limit has made it so loose, that it creates little incentive for domestic action.

Secondly, CDM, in combination with over-allocation, has undermined the overall capacity of the mechanisms to create real reductions. Between the surplus of EUAs, and the availability of cheap CERs, industries under the EU ETS had to make very little domestic changes to meet targets. And if we consider cases like the HFC CER ‘fraud’, where Chinese and Indian companies were producing more HCFC-22 to take advantage of CER revenues for the subsequent destruction of HCFC-23 byproduct (EIA, 2011). Moving forward will require higher standards regarding the environmental integrity of CDM projects, in order to guarantee the effectiveness of our strategies to stabilize CO2 concentrations.

Regardless of potential and actual problems associated with CERs in the EU ETS, the most cost effective path to low carbon intensive economies requires that ‘where-flexibility’ mechanisms like CDM. Cost constitutes a major barrier for adopting low carbon, and more efficient technologies, and compliance with measures can be increased if structures that allow us to take advantage of differences between marginal reductions costs, and incentivise action are accepted, supported.

Moreover, mechanisms that allow for the transfer of capital, and technology from developed countries to developing countries are necessary if we are going to have a real impact on global emissions targets. Additionally, the guidelines for CDM projects combine environmental requirements, with broader socioeconomic goals and helping to bridge the ‘development gap’ between countries of different economic capacity.

The future of CDM in the EU ETS is complicated, emissions trading, and CDM and JI are new, and we are still learning. The urgency of effective climate change mitigation requires mechanism like these in order to make a meaningful impact, and share the associated economic burden. Whether or not we like it, collaborative action is necessary, so itis time to iron out the wrinkles, and get to it.

Sources:

Environmental Investigation Agency (2011) Massive climate subsidies for HFCs industry to continue. . Retrieved 31 March 2014 from:

EU ETS (2013) CERs and ERUs market as from 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2014 from:

http://www.emissions-euets.com/cers-erus-market-as-from-2013

European Commission (2013) The EU Emissions Trading System. Retrieved 31 March 2014 from:

http://ec.europa.eu/clima/publications/docs/factsheet_ets_en.pdf

Piris, Pedro (2010) The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme: A Succinct Review, by Pedro Piris-Cabezas 2010.

UNFCCC Website, (Last updated March 2014) Clean Development Mechanism. Retrieved 31 March 2014 from:

http://cdm.unfccc.int/index.html

.png)

].gif)

.png)

].png)

].png)

].png)

.png)

].png)

.png)